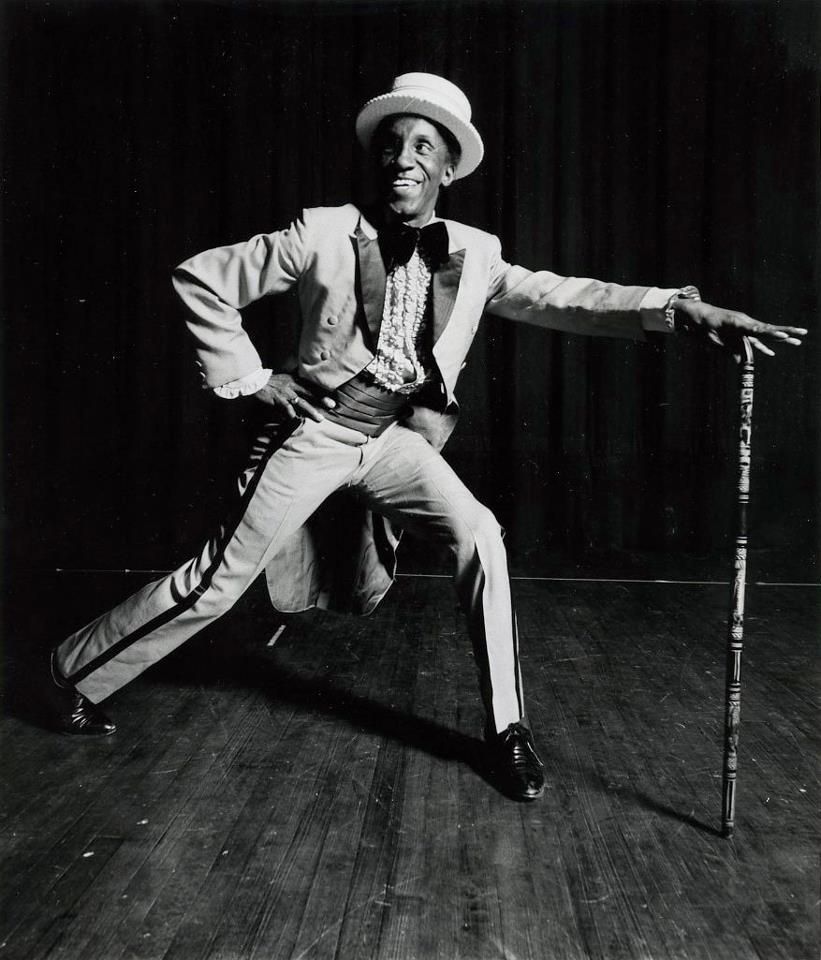

Lindy-hopping jazz dancer who choreographed the celebratory revue One Mo’ Time

The jazz dancer Pepsi Bethel began his career by founding his own performing company in the late 1930s. He ended it having restored the lindy hop – a slice of American culture involving energetic jiving -to fame on Broadway, taught at the Alvin Ailey school in New York and performed jazz dance across Africa.

Born in Greensboro, North Carolina, Pepsi was brought up by his grandmother, who gave him his nickname, after his parents separated. Before reaching his teens, he located his father, stationed with the US army in Washington, a reunion that led to regular visits to New York, where he discovered the Savoy Ballroom at the height of the swing era.

After gravitating towards the Tuesday night 400-Club sessions set aside for dedicated lindy hoppers, Pepsi created his own Southland-400 dance group with three couples in Greensboro. Importing Harlem standards of performance, dress and appearance, they quickly made a name for themselves, and danced everywhere – whether they were paid or not – often working with the most famous big bands. By 1942, their expertise was such that Pepsi and his partner Jerry De Moska took third place in New York’s premier lindy hopping contest, the Harvest Moon Ball at Madison Square Gardens.

Unable to resist the allure of the Savoy, Pepsi returned on his own the following year and came to the attention of Eunice Callen, of the elite swing dancing company, Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers. Callen found Pepsi roles in the Basin Street Revue at Broadway’s Roxy Theatre, and Born Happy, the show featuring Bill “Bojangles” Robinson that was touring California.

The Harvest Moon Ball brought Pepsi back to New York in 1946; he took second place with Leona Jones. Although now living in Greensboro, he kept returning to New York for gigs with Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers, although the influence of Marie Bryant, with whom he had worked in California, had begun to widen his horizons.

In 1954, Pepsi’s growing reputation helped him win a scholarship to New York’s Adelphi College dance school, where he studied ballet and modern dance for two years. He settled in New York in 1961, and, the following year, took a role on Broadway in the Tony award-winning Kwamina, choreographed by Agnes de Mille. In the 1960s and 1970s, he taught at the Alvin Ailey dance school.

But Pepsi did not neglect the lindy hop, or, rather, its authentic jazz dance context. In 1950, the Russian émigré dancer Mura Dehn had filmed him demonstrating various dance styles – from the cakewalk to the Jersey bounce – at the Savoy, a project that led to his inclusion in a series of Dehn’s lecture/demonstrations in the 1950s and 60s. In 1968-69, he also featured in the American Jazz Dance Theatre tour of Africa, organised by Dehn, which took in tap dancers, cake walkers and lindy hoppers.

Back in New York, Pepsi continued to teach at the Ailey school, and at the Clark Center dance studios on 8th Avenue, where he met Thelma Hill, another female mentor, who encouraged him to found a second company. Duly, in 1972, memories of the enthusiasm of African audiences, plus the dazzling expertise of his fellow performers, led Pepsi to launch his American Authentic Jazz Dance Company.

This was an extraordinary venture, going against the current African-American cultural tide, which gave a largely Africanist interpretation to black consciousness. Pepsi insisted on the validity, in terms of the African retention, of the African-American domestic tradition – from the minstrels of the 19th century to the lindy hop in the 1930s and 40s. Dancers like Alan Davidge and Tee Ross, plus Pepsi’s eclectic but inspired collation of dance techniques, enabled him to highlight the importance of dance forms which had been increasingly dismissed as mere “entertainment”.

The company’s success climaxed in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and paved the way for Pepsi’s notable choreography of Vernal Bagneris’s hit jazz revue, One Mo’ Time, set amidst the black vaudeville circuit of 1920s’ New Orleans. After a highly successful off-Broadway run, spin-offs in Europe and a filmed version in Vienna, the show made Broadway proper last year. There were further collaborations with Bagneris, including Staggerlee (1987).

Pepsi was always being asked to teach, but had grown sceptical of the work of dance colleges and their students. Asked, in the 1980s, about new dancers, he responded: “They’re looking for too much too quick. They want everything like instant coffee. Nothing works like that, not your mind, not your body, nothing.”

In 1986, however, he agreed to teach and choreograph my company, the Jiving Lindy Hoppers, in a production called That’s It!, at the Battersea arts centre, in south London. It was a tough, but immensely rewarding, experience that enabled the company to turn professional the following year.

In 1997, a disastrous fire at his apartment destroyed many of Pepsi’s records, after which he became a recluse. Eddie Robinson, another ex-pupil, who restaged his choreography for One Mo’ Time for the recent Broadway production, cared for him in his last years. Many other students returned, and kept visiting, right up until the end.

· Alfred ‘Pepsi’ Bethel, dancer, born August 31 1918; died August 30 2002

UPROOTED’S (the film) Cast of experts – Karen Hubbard – danced with Pepsi.If you’re passionate about jazz dance, our website is a treasure trove of resources. Delve into our comprehensive Jazz Dance Workshops, where beginners and seasoned dancers alike can learn new techniques and refine their skills. These workshops are designed to cater to a variety of skill levels, ensuring everyone can participate and grow. For those looking for a more immersive experience, our Jazz Dance Intensives 2023 and Jazz Dance Intensives 2024 offer a deeper dive into the world of jazz dance. These intensives are perfect for dancers who want to challenge themselves and achieve new heights in their dance journey. Both programs are taught by experienced instructors who are dedicated to helping you excel to your fullest potential.

Leave a Reply